Dying in the Middle Ages: the Great Pleague, © Museum Hameln

Dying in the Middle Ages

Rich and Poor

Inside the city walls the nobles mostly live in tower residences made of stone, with adjacent outbuildings. The rich live in stone- and large timber-framed houses. The poorer citizens live in simple wooden huts. Most houses have a well and a refuse pit, often situated very close together. Livestock is kept behind the houses, also the gardening patches. There is no running water. Waste disposal is a major problem. Here and there you find a primitive sewage system.

Many devastating fires, flood waters and epidemics plague the city. Hameln most probably also suffers from the Black Plague around 1350. Nursing the poor and sick is mostly the responsibility of the church, but in the 15th Century, normal citizens start getting involved. The first Poor House in the city is built. For contagious diseases a special “sick house” is erected in Wangelist.

The Great Plague

When the year 1349 was counted […], a widespread epidemic and deaths of people also began, such that no-one could remember or [knew] from hearsay of such great numbers of deaths. […] The people who died all died of boils and swollen glands under the arms and on the upper legs. And whoever had boils, who would then die, they died on the fourth day […]. It is also passed from one to another: In a house where there was a death, it seldom remained at one [death].

Fritsche Closener, Strasbourg Times, 1362

The bubonic plague

Toggenburg Bible, 1411

Around 1350, the whole of Europe was caught by a disease which killed a total of 25 million people. That a third of the population of Europe died is today disputed. But without doubt: in the 14th century, people were afflictedwith a highly infectious and incurable disease that until then had been unknown. Did the “Black Death” also reach Hamelin around 1350? Johann von Pohle reported in 1384 that he had written his diocese chronicle “after the epidemics”.

Print room. Berlin Public Museums

Doctor cuts open plague boils

Hans Folz, “Dictum of the Pestilence”, 1482

Medieval medicine had nothing to fight diseases like the plague. The treatment began with the symptoms, not the causes. Magical rituals and potions were among the therapies. In the Late Middle Ages, there was a widespread conviction, originating from ancient sources, that “miasma”, poisonous vapours from the earth, fostered infection. Not until the Early Modern Age were hygienic measures derived in the cities as a result of this.

Hildesheim Cathedral Library

Flagellant processions in Doornik

Aegidius Li Muisis, chronicle, around 1349

The plague was taken by contemporaries to be a punishment from God. The epidemic was interpreted as an apocalyptic sign of the imminent end of the world. It was a time of church service pleas and processions. In many places, processions of self-flagellators were reported: people in atonement processed through the cities, whipping themselves. They hoped to free themselves from their sins and avoid punishment.

Koninklijke Bibliotheek van België Brüssel

Nuns care for the sick in hospital

Jean Henry, Le Livre de Vie Active de l’Hôtel Dieu, around 1482

In the Middle Ages, care for the sick and poor was incumbent exclusively on the church. Church orders were founded which were primarily occupied with the establishment and maintenance of hospitals. Only in the Late Middle Ages did public institutions arise, usually from civic foundations.

Bridgeman Art Library Berlin

Hospitium Sanct. Spiritus or Holy Spirit

Paul Voigt, around 1900

In 1247, the foundation requested the city council and the citizens to support the “City Hospital” with small donations. In the 14th and 15th centuries, several poorhouses and hospitals were mentioned as being “guesthouses” in the city. The amalgamation of the institutions an die Heilig-Geist and Kapelle am Stadtrand probably only took place in the 16th century.

Saint George, © Museum Hameln

Saint George

Refurbished in 1730, Wangelist Chapel

According to legend – George fought a dragon and won. He was beheaded as a Christian martyr in the early 4th century. Since the Late Middle Ages, he has been honoured as a patron saint. Help is expected from him during times of fever and plague.

A wooden picture of St. George was said to have hung in the east wing of Wangelist Chapel until the 18th century. In 1730, it was replaced by this stone sculpture. It did not remain undamaged: in 1758, a French soldier cut off an arm of the knight.

Wangelist Chapel

Louis Horst, 1859

In 1469, a chapel was donated to Wangelist Infirmary. The aim was to provide the sick with their “own” church service outside of the city. The construction was spartan. The evening meal was given to the sick through a hole in the door. Supervision of the institution was led by the Hamelin bakers’ and shoemakers’ associations. Both groups also regularly donated physical goods to the sick: shoes and bread.

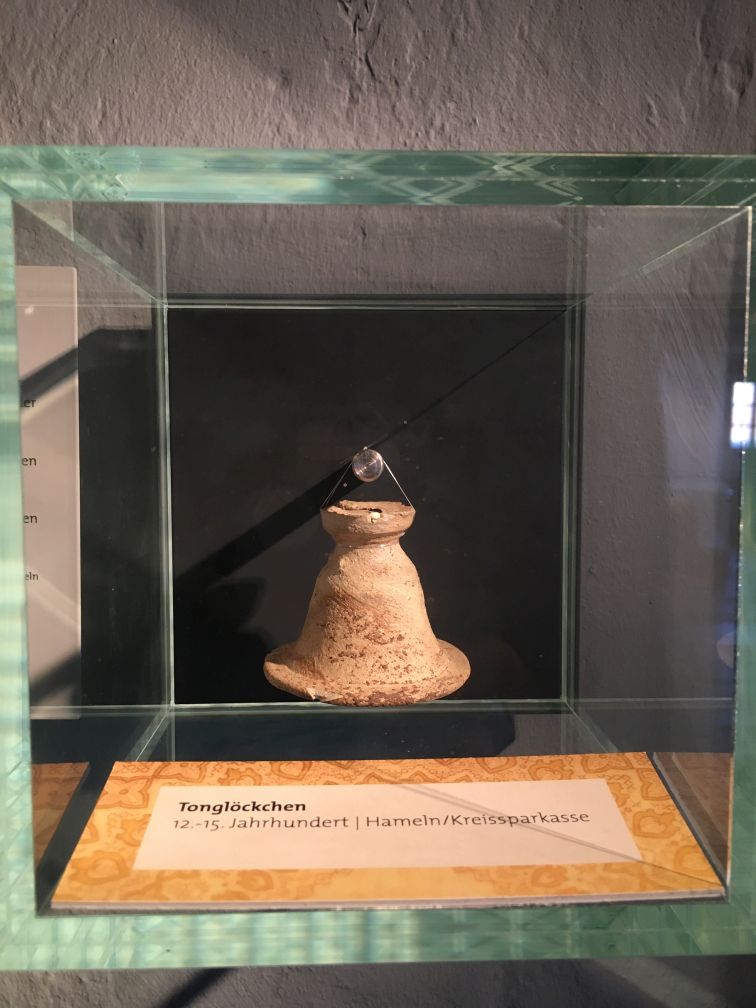

Chiming bell, © Museum Hameln

12th-15th century, Hamelin/Kreissparkasse 1987

Fear of infectious diseases played a major role in the Middle Ages. The sick had to declare their ailment, either visually or acoustically. Healthy people could then avoid them.

In medieval pictures, lepers are often represented with ringing bells warning of their arrival. The fear of infection was also the reason why the infirmary founded in Wangelist possessed its own chapel. The sick were meant not to attend services in churches in Hamelin.