Life in the Middle Ages

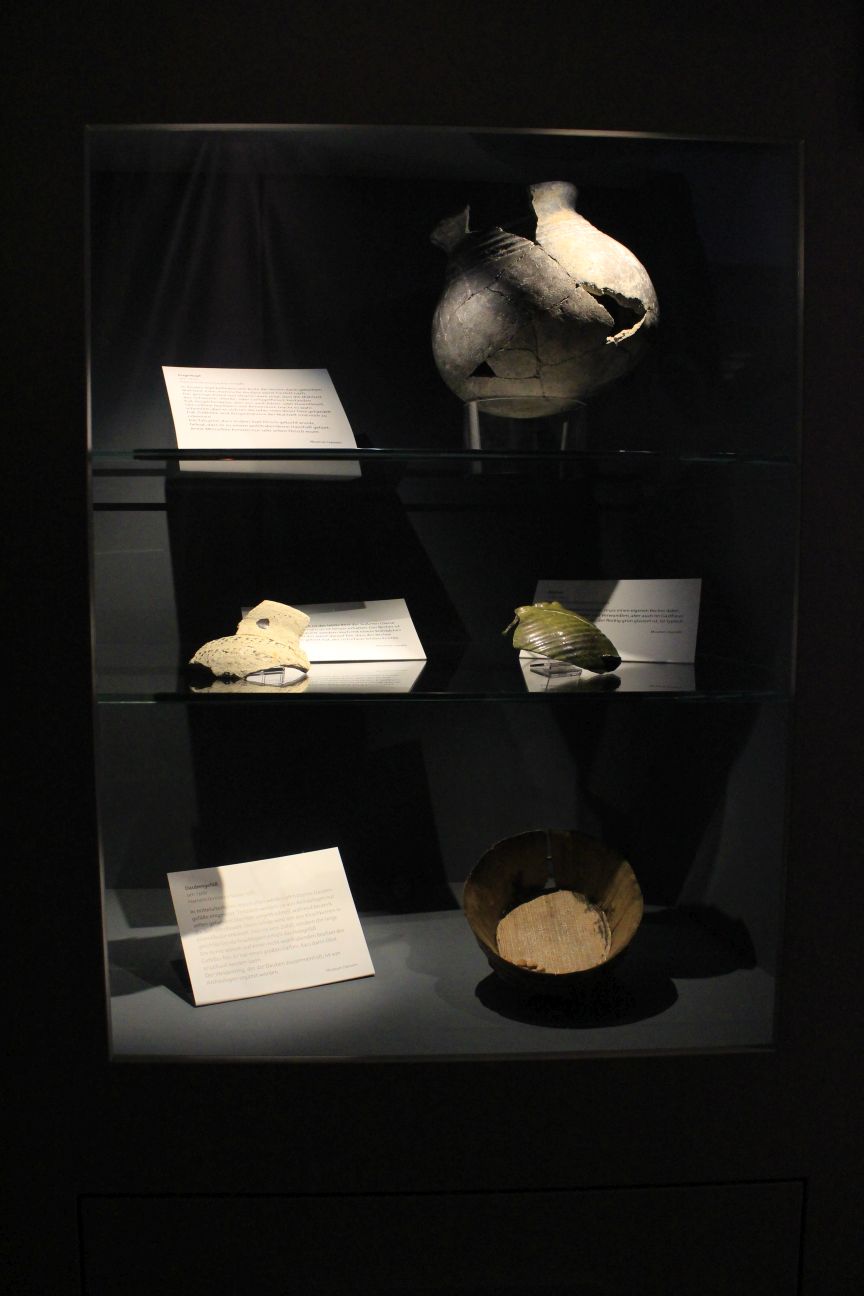

Rounded jar and wooden vessel, © Museum Hameln

Rounded jar

around 1200, Hamelin/Kreissparkasse 1987

The remains of the last meal cooked in it are found in this pot. A chemical analysis has proved the presence of animal fat. The low proportion of stearic acid shows that the meal consisted of pork, horse or poultry meat, but possibly also bear or rabbit. The rare evidence of behenic acid makes it probable that it was the liver of one of these animals. The filling level and traces of pouring the meal are still recognisable.

The fact that meat was cooked in the pot proves that it belonged to a wealthier household. Poor people could only eat meat very seldomly.

Cup fragment

1200-1250, Hamelin?

The small dark spot is the last of the remaining external glaze of the cup. The internal glaze is better preserved. The cup is not only double-glazed, but also decorated with a small rolling wheel. All of which indicates that the cup once belonged to someone who could afford expensive things.

Cup

1250-1300, Hamelin/Stadtsparkasse 1961

If someone wanted to drink, they had to have their own cup – with friends and relatives, but also at the inn. The design of the cup, which is glazed spotted green, was typical in northern Germany.

Stave-built wodden vessel

around 1300, Hamelin/Kreissparkasse 1987

In households in the Middle Ages, wooden stave-built containers were often used. They are nevertheless found only seldomly by archaeologists: wood decays quickly, while ceramic stands the test of time. This bowl was discovered with cherry stones in a sewer. This is no coincidence, since the constant, lasting dampness preserved the wooden container.

The cherry stones indicate a very wealthy owner of the container: they had such a large garden that fruit could be grown there.

The willow ring holding the staves together was added by archaeologists.

Knives, © Museum Hameln

Knife

14th century, Hamelin/Thietorstraße 1978

The knife is decorated in the style of a roller stamp pattern and has a wave pattern in the hilt. It is thus oriented to the decoration of ceramics of this time.

There were very individual variations in blade shape in the Middle Ages. The grip was also designed according to taste and fashion. The often drawn and used knife was also a status symbol. The materials and workmanship demonstrate the wealth of the bearer.

Knife blade and grip

15th century, Hamelin/Wangelist 1982

Knives were among the most important multi-tools in the Middle Ages. They were constantly carried along and serve the most varied of purposes. They were tools, cutlery, household appliances and weapons all-in-one.

The most common form in the Middle Ages was the horizontal tang knife. The blade ends in a spike and was mounted in a handle – usually made of wood or horn. The knife shape with its straight snap-off blade back is in the tradition of Saxon blades from the Migration Period.

Life in the Middle Ages: a wooden calyx, © Museum Hameln

Wooden calyx

13th-15th century, Hamelin/Kopmanshof 1983

The calyx has been turned from a block of hardwood. This was a difficult task, since the soft wood is hard to cut. It could be lime, walnut, cherry, plum, sycamore or beech wood.

Turned vessels are rare and correspondingly valuable.

Ballock knife with sheath

around 1300, Hamelin/Kreissparkasse 1987

The ballock knife was a typical weapon of the wealthy and nobility, but was also carried by members of other social classes. The name comes from the two side bulges on the lower gripping end, which have an implied ball shape. Researchers believe that they take the shape of testicles and thus emphasised the status of the bearer.

The sharp blade could be used against armed opponents. It could penetrate chain mail, and the diamond cross section, which widens towards the hilt, could pierce armour.

The Hamelin dagger with lily-decorated sheath is an especially well-preserved and early piece. It was discovered along with many organic finds in a sewer. How could such a valuable dagger go missing? Was the owner so drunk that he didn’t remember the next day where he had relieved himself?

Spurs and a horseshoe, © Museum Hameln

Spurs

11th-13th century, Hamelin/Ützenburg 1934

The spurs are equipped with a pyramid-shaped tip. They can thus be dated. Earlier spurs had a conical tip.

Spurs did not only have the purely practical function of steering a horse, they were also a sign of social prestige. Not every man had a riding horse in the Middle Ages and money for the equipment. The wearer of the spurs may have been a knight.

Spurs

15th century

The shape of the spurs was subject to waves of fashion like clothing and haircuts. This curved form was clearly from the Late Middle Ages.

The shape of the bracket indicates that it could not have been fastened with a strap over a boot. The spurs belonged to the military equipment of a knight.

Horseshoe

11th/13th century, Hamelin/Pyrmonter Straße 1954

Scattered horseshoes, dating from the 9th century onwards, have been archaeologically proven. Horseshoes enabled the horse to be used for longer. Especially on stony ground, hooves were worn down very quickly or damaged. In the Early Middle Ages, protective horseshoes with straps were attached. Studs made far more durable attachments. This method was costly, however, and so was used by few riders. Agricultural working animals were almost never studded at this time.

If the horseshoes were to be nailed, they had to be equipped with holes. These were driven into the glowing iron with a wedge-shaped pin. The wavy edge was thereby produced.

Hand mill, © Museum Hameln

Hand mill (quern)

12th century | undated, Hamelin/ECE Centre 2006

A hand mill consists of an upper and lower stone. The upper stone – grinder – moves while the lower stone remains still. These parts unfortunately do not belong together, but illustrate the principle.

Hand mills were standard kitchen equipment right into the Modern Age. Grain was among the main sources of nutrition for people. Hand mills delivered whole grains for household consumption.

Larger quantities of flour were milled in water mills. The landowner had a monopoly on the milling of flour. The people were obliged to have their grain milled in a certain mill in return for levies. This compulsory form of milling could be avoided with a hand mill. However, this is only practical for smaller amounts.