The unknown neighbour, © Museum Hameln

The Unknown Neighbour

3rd March, 1690: After many weeks of marching, 102 Frenchmen arrive in Hameln. In the next few months more follow. These are Huguenots, followers of the reformed teachings of Calvin. They had to flee their country, because they were not allowed to practise their religion anymore.

Duke Ernst August permits them to settle in Hameln, allowing them to establish their own church. We don’t know whether this is an act of religious tolerance, or the fact that the duke hopes to gain competent craftsmen free of charge. In 1733 more religious refugees arrive from Brechtesgaden. This has an enriching influence on the spiritual life of the church. From 1713, a garrison church also provides for the spiritual needs of the soldiers and their families. Many citizens of Hameln are attracted to these pious communities. In 1778 a Freemason Lodge is founded, where thoughts and ideas can circulate freely among like-minded people. Still, one exception remains: the Jews. They are excluded and continue to be dependent on the protection of the dukes.

Karl Philipp Moritz

N.N., around 1780

Karl Philipp Moritz was born on 15th September 1756 in Hamelin as the son of the military musician Johann Gottlieb Moritz and his wife Dorothea. His early childhood in Hamelin was shaped by life in the fortress and the unhappy marriage of his parents. His father was devoted to quietism: This special form of Christian mysticism underwent a Renaissance at the end of the 18th century. Contrary to the ideals of the Enlightenment, the quietists demanded the total self-abandonment of the individual. The individual should completely relinquish their passions and personal inclinations. After a few years, Moritz moved with his mother from Hamelin to a village close by and then to Hanover. Moritz received his school education here and laid the foundations of his later career as a writer.

Living expenses receipt

signed by Dorothea Moritz, 1756

Karl Philipp Moritz left behind no trace in Hamelin. Neither could his residence be exactly located nor have objects from his inheritance been preserved. In the birth year of the poet, his mother Dorothea Moritz certified a receipt for living expenses. This money was paid to soldiers without barracks accommodation to rent their own place to live. It was sometimes paid to the wives of the soldiers.

Hamelin City Archive

In P[yrmont], a place renowned for its wellspring, lived in the year 1756 to his good fortune a nobleman, who was the chief of a sect in Germany known as the quietists or separatists whose teachings are primarily contained in the texts of Mad[ame] Guion, a well-known mystic […]. Mr v[on] F[leischbein], so was the nobleman called, lived here isolated from all other inhabitants of the place and likewise their religion, manners and customs, since his house was separated from theirs by a high wall which surrounded it on all sides. This house was like a little republic where certainly a quite different constitution was in place than anywhere else in all of the land around it. The entire household down to the lowliest servants clearly consisted of a kind of people whose efforts were only or seemed only to be focused on entering into “nothingness” (as Mad[ame] Guion calls it), “extinguishing” all passion and eradicating all “selfhood”.

All of these persons assembled once a day in a large room of the house for a type of church service which Mr v[on] F[leischbein] himself organised and which consisted of them all sitting around a table with their eyes closed, their heads lying on the table and waiting for half an hour to see if they possibly would perceive the voice of God or the “inner word”. If someone experienced something, they would tell the others. Mr v[on] F[leischbein] also determined the reading of his people, and when the servants or maids had a quarter of an hour to spare they were seen with nothing other than one of Mad[ame] Guion’s texts on “inner prayer” or the like in their hand, sitting and reading in a contemplative position. Everything down to the smallest domestic duties in this house had a serious, strict and solemn aspect. In all facial expressions could be read “renouncement” and “denial”, and in all behaviour “abandonment of self” and “entering into nothingness”.

Karl Philipp Moritz, Anton Reiser, 1785

Salzburg (Platzstraße 6)

N.N., 1980

The first emigrants from Berchtesgaden arrived on 5th July 1733 in Hamelin. Insofar as they were manual labourers, these “Salzburgers” were set to work in the construction of watergates. A total of 24 people were accepted. They were accommodated in a timbered house specially built for them. It was thereafter known as the Salzburger House or “Salzburg” for short.

French reformation church

Bäckerstraße 28-30, Paul Voigt, around 1900

The refugees formed their own French-speaking reformation community in Hamelin. In 1699, they received from the Prince a church and semi-detached house for their two pastors. From the mid-18th century, the religious and cultural separateness of the religious refugees was gradually eroded. They integrated.

French poorhouse

Alte Marktstraße 16, Paul Voigt, around 1900

At first, due to the rights granted to them by the Prince, the Huguenots formed an ecclesiastically, economically and culturally independent community. They also took responsibility for the social care of the members of their colony themselves. Thus they ran their own poorhouse. The special privileges were in fact abolished in 1706. In ecclesiastical and cultural matters, however, the idiosyncrasies were preserved for longer. Integration of the French into the Hamelin citizenry took place step by step.

Salzburg emigrants

Elias Back, 1732

Because the Archbishop of Salzburg and the Prince-Provost of Berchtesgaden wanted to implement the Counter-Reformation in their regions using force, thousands of Protestants left their homelands. Most of them were granted admission to the Protestant Principalities of Germany. On the invitation of George II, several hundred of them were also allowed to settle in the Principality of Hanover.

Berlin Public Museums, Lipperheidesche Art Library Costume Library

Huguenots in Hamelin, © Museum Hameln

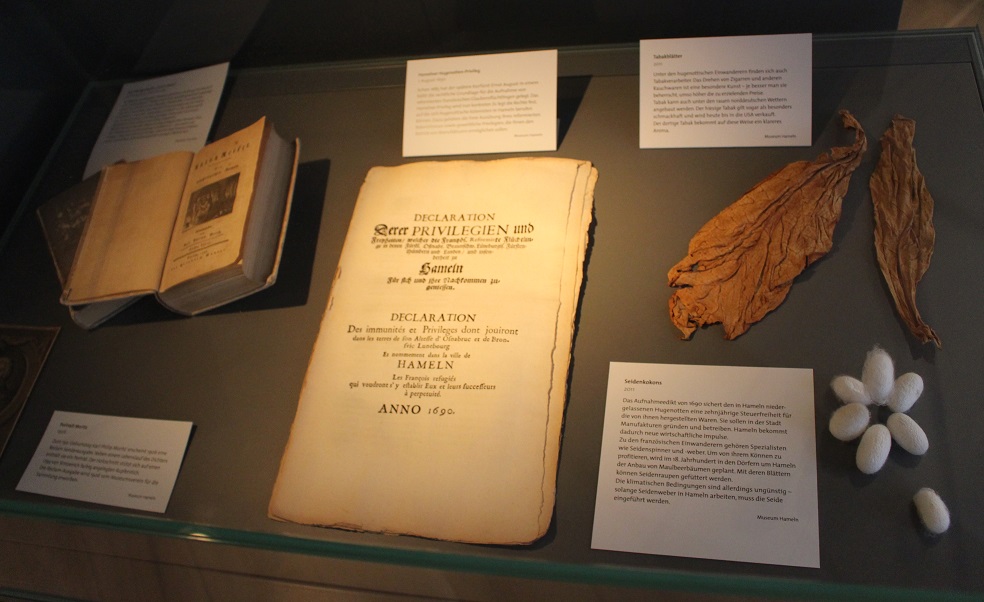

Hamelin Huguenot privileges

1st August 1690

In 1685, the subsequent Prince Ernst August laid the legal foundations for the acceptance of reformed French religious refugees by edict. The Hamelin privileges now became more specific: It laid down the rights to which Huguenot colonists in Hamelin could refer. Among these was the free practice of their reformed faith, as well as commercial privileges to enable them to undertake manufacturing.

Silk cocoons

2011

The admission edict of 1690 secured a ten-year tax exemption for the manufactured goods of Huguenots settled in Hamelin. They were encouraged to establish and run manufacturing enterprises in the city. Hamelin would thereby receive a new economic stimulus.

There were specialists such as silk spinners and weavers among the French immigrants. To profit from their abilities, in the 18th century the cultivation of mulberry trees was planned in the villages around Hamelin. Silk worms could be fed with their leaves.

The climatic conditions were unfavourable, however – so as long as silk weavers worked in Hamelin, the silk had to be imported.

Tobacco leaves

2011

There were also tobacco manufacturers among the Huguenot immigrants. The rolling of cigars and other tobacco goods is a special art – the better it is mastered, the higher the prices received.

Tobacco can also be grown under the harsh northern German weather conditions. The local tobacco is especially flavourful and is sold today as far away as the USA. The tobacco there thus has a clearer aroma.

Karl Philipp Moritz, “Anton Reiser”

First editions, 1785 and 1790

Among Moritz’s most important works are “Andreas Hartknopf” and “Anton Reiser”. Both are highly autobiographical. Reiser appears in four volumes and is unfinished. The book chronicles Moritz’s memories of his early childhood in Hamelin. He portrays vividly the living environment in the city fortress and spiritual atmosphere of the devout circle of quietists to which his father belonged.

Moritz described the work as a psychological novel. From the distance of a third person narrative, he depicts – 100 years before Freud – a kind of case history, namely the inner experiences of a perturbed, disoriented young person.

Portrait of Moritz

1906

A Reclam special edition appeared in 1906 on the 150th birthday of Karl Philipp Moritz. It contains a portrait in addition to a life history of the poet. The wooden carving is based on a copper engraving made in colour by Sintzenich in 1793.

The Reclam edition was acquired in 1906 by the Museum Society for its collection.

Glikl of Hamelin, © Museum Hameln

Everyone knows what Hamelin is compared to Hamburg. […] Hamelin is a paltry, boring place.

Glikl, daughter of Judah Leib, named “Glückel of Hamelin”, around 1690

Glikl, daughter of Juda Leib

Glikl was born at the end of 1647 in Hamburg as the daughter of a Jewish trader. She only had a short childhood. Before she turned twelve, her father engaged her to Chaijm, the son of the businessman Joseph ben Baruch ha-Levi (Joseph Goldschmidt) from Hamelin. Two years later, the marriage took place in Hamelin. Glikl now lived together with her husband Chaijm with the parents-in-law in Hamelin. They only remained in the city on the Weser for a year. Then the young married couple moved to Glikl’s parents in Hamburg. Here Chaijm built his own trading company. One evening in January 1689, he unfortunately slipped and died a few days later. The sadness over his death led Glikl to pen her own life story. Composed in Yiddish, they are the first known written memoirs of a woman.

The name “Glückel of Hamelin” was only given to the author in 1896 by the first publisher of her memoirs.

Jew and Jewess

Christoph Weigel, Nuremberg, 1703

There is no portrait of the world renowned businesswoman “Glückel” of Hamelin. We must form our own picture of her.

The copper engraving shows a man and woman in clothing worn by Jews in Frankfurt in around 1700. Glikl lived at this time in Metz and was married for the second time to the banker Cerf Levy.

Duke August Library, Wolfenbüttel

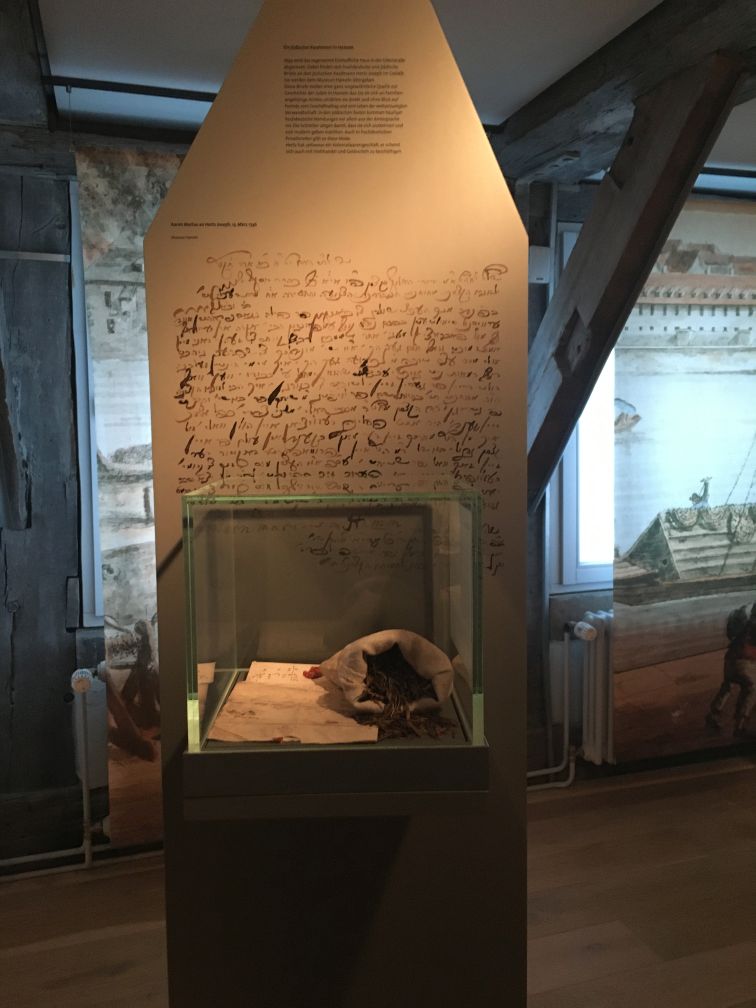

A jewish businessman in Hamelin, © Museum Hameln

Letter (reproduction)

1760s

Josef Hertz wrote in Yiddish with Hebrew letters. He also used High German phrases – the family did not distance itself from its surroundings.

The Jews in Hamelin were afraid of attacks by their neighbours: “We lived in great fear and terror during this time. There was no moment in which one did not hear all manner of gossip. […] Detmold was crazy yesterday. Now one hears that Hamelin joined in. God will turn all things to the good, so that peace will reign on earth, and once again things will be in harmony.”

The tea that Hertz sold in Hamelin was purchased by him in Bremen. Mostly green tea was consumed.

A Jewish businessman in Hamelin

The so-called Eickhoff House in Osterstraße was demolished in 1899. Letters in High German and Yiddish to the Jewish businessman Hertz Joseph were found in the woodwork. They were passed on to Hamelin Museum.

These letters represent a quite unusual source of Jewish history in Hamelin. Since they were written to family members, they relate daily business and the life of widely-branched kinsfolk directly and without consideration of outsiders. High German phrases, mostly from official language, occur frequently in the Yiddish texts. The writers thus showed that they were knowledgeable and wanted to appear modern. This trend also appears in High German private letters.

Hertz temporarily had a colonial goods business, and he also seemed to work in livestock trading and money lending.

Aaron Marius to Hertz Joseph, 13th March 1746